In this blog post, I describe my journey with Out of Eden Learn as an educator in a learning context called The Aspiring Phoenix Foundation (TAPF), an Acton Academy, where “studios” replace classrooms and learner-driven environments are core to our mission. Out of Eden Learn (OOEL) offered new opportunities and a new venue for the children to lead their learning. While the context in which I work is unique, our practices and journey with OOEL are relevant to more traditional classrooms and schools.

When a close friend from college, who is also an educator and life-long learner, recommended OOEL, I was eager to check it out. I was so pleased that the OOEL materials and resources were set out in such a user-friendly way. I was certain that our learners would be able to take the lead before the end of the year. As a guide, my role is to set the stage for the children’s learning, give them the tools and resources to accomplish the objectives, and stand aside. Each day, we have “Launches” in the morning and after lunch. The aim is to tell a story, pose a question, or make a statement and allow time for Socratic debate. There are no “right” or “wrong” answers.

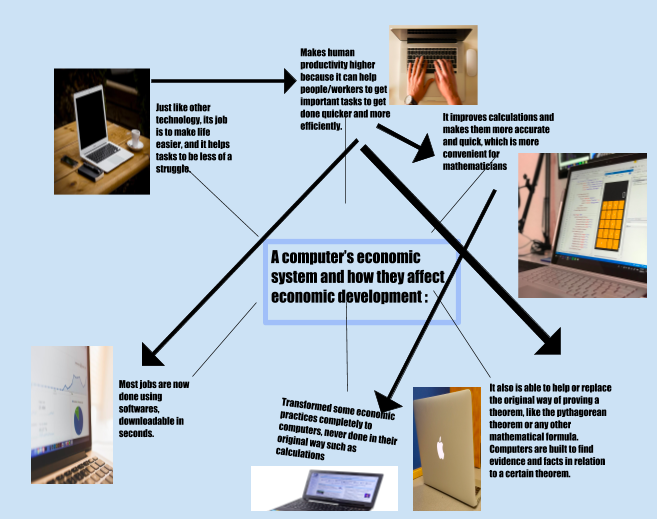

In our Elementary Studio (ES), 7 learners between 8-12 years old participated in OOEL for their Civilization Time, twice a week for 45-60-minute slots. We function as a multi-age studio, rather than dividing the children by age and grade level. Peer-to-peer learning is such a powerful tool, given each of us have various degrees of strengths and weaknesses. In my experience, age hasn’t been the defining factor of mastery or maturity; rather, intrinsic curiosity that is allowed to follow its path normally leads to even more opportunities to learn. On our campus, our learners immerse themselves in their roles as an anthropologists /scientists /investigators/authors/photographer, depending on the learning adventure and challenge. In our program, our goal is for curious investigation and deep exploration to become part of the joyous cycle of a lifelong learning.

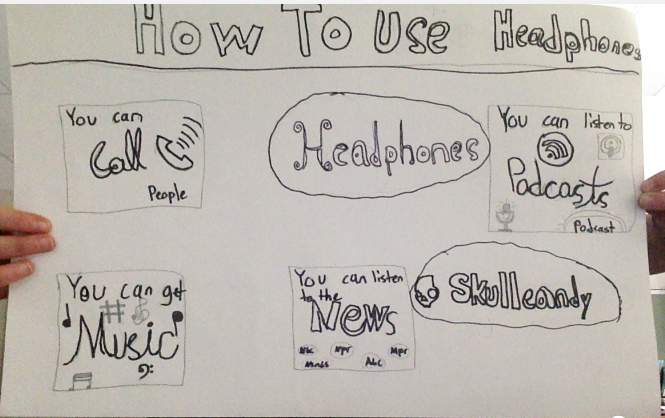

The students were intrigued with the idea of doing “The Present and the Local” OOEL learning journey, and decided to undertake it. In the beginning, we watched the videos together, discussed together the target Footstep for the day, and then they organized themselves to work in pairs or small groups, occasionally someone would work alone for a bit, then come back to join after they accomplished their personal goal. The Dialogue Toolkit (DTK) easily integrated into the learners’ everyday language since it helped them follow the Rules of Engagement, which are set by the learners at TAPF at the beginning of the year. The rules include stating “I agree/I disagree with… because…”, linking their comment to the previous statement, and not interrupting the person who is speaking. The children hold each other accountable according to their “Studio Contract” that functions as their constitution. They wrote the document themselves and they can adapt it as they see necessary to govern their Studio. Everyone had access to a digital copy of the Dialogue Toolkit in their online portfolio, and a large poster of it was prominently displayed in a central location for easy reference. Frequently, I witnessed the children looking at the poster or finding it in their portfolio. I saw them use phrases from the Dialogue Toolkit such as “I was surprised by…” and “Could you tell me more about…?”, when they were asking each other for clarifications during group discussions after watching the videos together in Part 1 and when extending the dialogue through replies to online posts. The children actively listened to their peers and new friends from their “walking party” while strengthening their interpersonal communication skills.

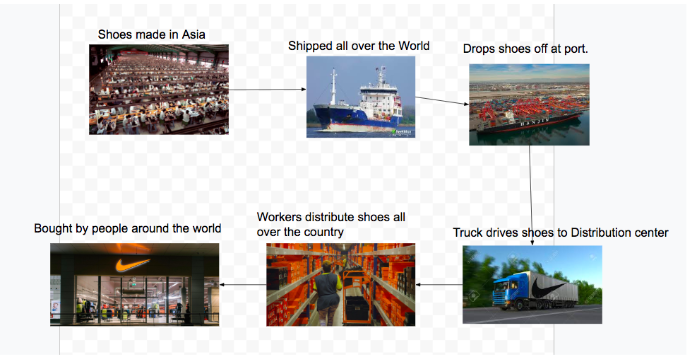

As they participated in OOEL Core Learning Journey 1: The Present and the Local, I observed how the learners became engaged with the content and how it spurred further inquiry and investigations. It was thrilling to watch them dive into a topic and whole-heartedly explore it. The Neighborhood Walks footstep was a Studio favorite. The children were clearly happy to be outdoors and doing something exciting. They enjoyed investigating their surroundings while looking closely at the neighborhood for “evidence” to answer the questions from OOEL. As a group, they clearly were enjoying themselves: themselves in discussions about geography, current events, and, in doing so, developed their skills of looking slowly and listening actively.

To wrap up each Civilization Time, learners shared their reflections as a whole group, offering feedback, and highlighting strategies that had worked for them to keep on track with their daily and weekly goals. When I began asking who would like to lead the closing reflection after these sessions, many eager volunteers emerged. It was time to let them begin taking over and closing reflection, which turned out to be a simple process it was the most similar to their launch process, and Rules of Engagement with DTK support. For example, when the Civ Time Leader gathered the group at the end of a time-block, they would pose a general reflection question, like “What was the most interesting thing you discovered today when looking closely? What is your best “good question?”, then proceeded to moderate the conversation as they do in their regular discussions, weaving in DTK language and strategies to connect, notice, and share.

When we embarked on our second OOEL adventure, an Introduction to Planetary Health, I asked for a volunteer to lead Step 1 and someone to lead the Closing Reflection. There were several volunteers and as per our custom, a vote was held to decide who would be leading Step 1 and who would wrap up our OOEL Time. I took my lead from the learners; they gradually took over until they were running it all. I am present on our Neighborhood Walks to ensure everyone’s safety and security while exploring off-campus; otherwise, the learners are running the show. They schedule when we go on Neighborhood Walks, and they have lively discussions as we walk around our community.

In the future, I will continue to stand back and allow the learners to lead OOEL. It builds their self-confidence, encourages them to put their theoretical knowledge in practice, and helps them reflect on how history and the present intersect in their lives. By taking ownership of their education, the children deepen their understanding of the topics and take meaningful steps towards their life-long learning journey. Using OOEL with an increasing sense of autonomy for students has supported many moments that will keep them curious about the world around them, encourage them to invent, innovate and create, then pursue how to “fail forward” the next time to constantly seek to improve themselves and the world around them. Although my learning context may be unique, educators in any context can have their learners take the lead with OOEL and beyond.

The new COVID-19 reality has given us some hiccups for sure, however, I’m proud of our learners and their resilience. When we shifted from on-campus meetings to completely virtual interactions in mid-March, the transition was as smooth as it could be considering it happened over the weekend. Our plan is to continue with our OOEL Journeys. It’s a great opportunity to interact with other learners across the globe and exchange stories about how they’ve been impacted too. Overall, our little community has been flexible, continues to adapt according to updated COVID-19 guidelines, and is finding its own way to thrive.

——————————————————————————————————————–Alexis Cole is co-founder, learning arc designer, and guide at The Aspiring Phoenix Foundation (formerly Liberty Leadership), an Acton Academy affiliate in Bel Air, Maryland. She holds an MA in Curriculum and Instruction from Arizona State University and BA in Sociology from Taylor University. When she isn’t working on changing mindsets about education, she loves reading, cooking, gardening, crafts, and music. Travel is usually on the top of the list, but it has been quarantined for the moment.

-

-

-

Support PZ's Reach