This post was co-authored by Susie Blair and Carrie James.

We recently announced the expansion of Out of Eden Learn’s online Dialogue Toolkit to include three new dialogue tools: POV, Challenge, and Name.

The impetus behind these new tools is to support students to practice dialogue strategies that can deepen their conversations and, in turn, their understandings of their own and others’ stances on meaningful issues.

The impetus behind these new tools is to support students to practice dialogue strategies that can deepen their conversations and, in turn, their understandings of their own and others’ stances on meaningful issues.

In this post, we provide examples of how OOEL students have used these dialogue moves. The student work we share is drawn from a pilot we carried out with one walking party (online learning group) taking part in our Stories of Human Migration curriculum in the spring of 2018. The pilot included students and educators in five classrooms in diverse contexts in the United States and one classroom in Australia.

For each move below, we share a few different ways in which students put the move into action. We then point to insights from pre- and post-surveys with students and conversations with educators, offering specific suggestions to support students in their use of each move.

The POV (point of view) move is an opportunity for students to express their ideas and opinions to an authentic audience of young people whose backgrounds (and possibly viewpoints) may be different to their own. In our pilot walking party, we noticed students using this move to share their perspectives on a variety of themes prompted by the curriculum—including “everyday borders,” media accounts of migration, political discourse around migration, and other topics relevant to migration and students’ related lived experiences.

The POV (point of view) move is an opportunity for students to express their ideas and opinions to an authentic audience of young people whose backgrounds (and possibly viewpoints) may be different to their own. In our pilot walking party, we noticed students using this move to share their perspectives on a variety of themes prompted by the curriculum—including “everyday borders,” media accounts of migration, political discourse around migration, and other topics relevant to migration and students’ related lived experiences.

One student’s Everyday Borders post raised the perspective that social media can erect boundaries in communication because of the absence of facial expression and tone. In response, student Lindashi acknowledged the original poster’s perspective and offered a similar POV:

I completely understand people often communicate with each other on social media. I think we should have more face-to-face communication. Therefore, It can improve the relationship between people. – Lindashi (Adelaide, Australia) commenting on LindaZ’s “Everyday Borders” post

In a later comment, a student from the U.S. shared an example of a different border that was more salient to his experience:

In my point of view it is a barrier to speak a different language because it’s hard to communicate with others. When I was younger going to school was hard because I didn’t understand English which was a big barrier for me. – CM18 (Oregon, United States) commenting on LindaZ’s “Everyday Borders” post

In this comment, CM18 is drawing on his personal experience as a young English Language Learner as the basis of his stated POV. While we do not require that Out of Eden Learn students “back up” their points of view with specific details of their lives that may be influencing their perspectives (though we do explicitly invite them to do so with our new Name dialogue tool, discussed below) we are encouraged by the fact that some students feel comfortable enough on our platform to share such personal anecdotes.

Our Migration in the Media footstep activity—which involves comparing two journalistic pieces about migration—invites students to interpret and raise questions about media representations of human migration. In doing so, they often express their stances on the author’s handling of the topic itself, stating their own POV in opposition and starting a “dialogue” between themselves and the author.

For example, one student explored how images of migrants used in news articles may reflect particular attitudes about migrants in the United States, then shared her own POV on the matter:

Every immigrant should be seen as a part of our community and no person can be illegal. I do believe the photographers had the same ideas I had when they took their images. – Angel8all, New Mexico, US

Educators reported that although sharing a POV (especially on a public issue or topic that might be sensitive) did not feel appropriate or warranted across all Stories of Human Migration activities and discussions, students did practice the move in different ways (as illustrated in the examples above). These students’ use of intentionally careful language appears to promote a positive tone in their discussions. In that spirit, the current iteration of our Dialogue Toolkit includes suggested sentence starters for the POV tool—for example, “From my perspective…” and, “Some argue that… Others say…. In my opinion…”

The Challenge move is intended to push dialogue to go deeper as a means of raising critical questions—albeit while maintaining a constructive, respectful tone. We encourage students to use the Challenge move not only to challenge one another’s POVs, but also to challenge narratives presented by various media sources as part of our Migration in the Media activity.

For example, in her original post, oReOs4LiFe expressed concern over the absence of refugees’ voices and perspectives:

While this fairly unbiased article gives insight into the diplomacy side of the story, and what the U.S. and Mexican governments have done to combat the issue, the voices of the migrants themselves seem to be absent from this story. There are quotes from the U.S. president, an administrator from the Agency for International Development, and also a member of an independent think tank, but none from the people that the measures taken will directly impact. Although they are a large part of the story, there have been no migrants or relatives of migrants interviewed on how this will affect them. I feel that the migrants, not just in this story but in this topic in general, are being treated like animals that have escaped their cages and are now trying to be shoved back in. –oReOs4LiFe, Maine, US

Like oReOs4LiFe, a student in Oregon shared a critical perspective on the article she examined about refugees. Taking care to own it as her “own point of view,” this student similarly pointed to concerns about missing perspectives:

What I can say from my own point of view [is that] this writer was very blunt and insensitive with the word choice. I feel the way I feel because this article is suppose to be in between, yet I see no in-depth refugee interview, and I think that there should be because this is a article about the people. – Alexis, Oregon, US

As with the previous example, this excerpt serves as an example of both the POV and Challenge moves, as Alexis offers her contrasting point of view as a means to challenge both the tone and substance of the piece she examined. Alexis is also careful to reiterate that she is speaking on only her own behalf—”What I can say from my own point of view”—reflecting that she is aware that her opinion may not be shared by all of her walking partners. This student also is explicit when providing evidence to support her opinion, using the phrase “I feel the way I feel because…”

While educators reported that their students were often hesitant to use the Challenge move in relation to other youths’ perspectives, some tried out the move when commenting on their peers’ work. Lizcheng, a learner in Adelaide, Australia, appeared to carefully “Challenge” some claims made about the usefulness of social boundaries in another student’s Everyday Borders post:

And by your last sentence, could you please give some examples of what lessons can boundary teach us? I can fully understand that you want to hide sometimes to avoid those judgements and questions, but I think sometimes [facing] those judgements straightly and [using] actions to prove your ability might be a better way; you will find the people who truly know you along the way. – lizcheng (Adelaide, Australia) commenting on oReOs4LiFe’s “Everyday Borders” post

Here, lizcheng makes a point to find some common ground with her dialogue partner, stating that she “can fully understand” their point of view on social boundaries yet ultimately disagrees, asking for supporting examples of her walking partners’ claim that boundaries can “teach us lessons” and offering her own perspective as an alternative. This use of the move reflects a sensitivity to tone and tact, a theme that surfaced prominently in student feedback collected before and after our pilot via surveys; a large portion of respondents advised that an online commenter remain respectful, non judgmental, and kind when challenging another’s POV online.

While it is certainly heartening that students are careful to practice politeness when using the Challenge in online spaces like Out of Eden Learn, it is important that this isn’t overemphasized to the point where dialoguers feel like they can’t disagree for fear of being considered rude. To preempt this potential roadblock, we have crafted sentence starting prompts like “Although I appreciate your point of view, I see it differently. I think that…” and “Another way of looking at it is…” to equip learners with concrete language with which to respectfully—yet firmly—challenge one another’s viewpoints. Additionally, some educators provided in-class time for students to draft comments, get feedback, and revise them before posting on the platform – offering additional opportunities for reflection and feedback on tone.

The Name move asks students to explore and make connections between their POVs and their backgrounds, experiences, identities, or the places they live and/or have lived. This move was designed to prompt learners to critically (and perhaps meta-cognitively) think about where their opinions and perspectives are coming from and to unpack the various pieces of their identity that may be at play (in the realm of social science research methodology, this concept is referred to as positionality).

The Name move asks students to explore and make connections between their POVs and their backgrounds, experiences, identities, or the places they live and/or have lived. This move was designed to prompt learners to critically (and perhaps meta-cognitively) think about where their opinions and perspectives are coming from and to unpack the various pieces of their identity that may be at play (in the realm of social science research methodology, this concept is referred to as positionality).

Some students use this move to point to important features of their family’s and/or their own experiences that shape their perspectives on—and emotions related to—particular issues.

For example, one student used the Name tool in her response to a “two-voice” poem by another student in Oregon in which they juxtaposed quotes from President Trump with excerpts from immigrant stories

Hi jg00, I really liked your poem. It kind of hit home because my parents and most of my family are Mexican immigrants. I really liked how one of the voices in your post was the opinion or point of view of Trump and the other voice was an immigrant. – Lisbon (New Mexico, US) commenting on jg00’s “Migration in the Media” post

Lisbon traces her emotional response to jg00’s poem to an important aspect of her identity: being a second-generation immigrant. A crucial component of Out of Eden Learn is that students are required to remain pseudonymous, not sharing any identifiable or traceable information (including personal names, specific locations, or photographs of themselves). Some students report that pseudonymity is a positive affordance of Out of Eden Learn—they can feel freer to be themselves with less fears of being judged or stereotyped. By requiring pseudonymity among Out of Eden Learn students, we hope that they can feel free to share any and all parts of their identities that they feel are important and would like to share with others, rather than others making assumptions about them based on their outward appearance or presentation.

In contrast to Lisbon’s example, other students used the Name move to indicate the limits of their understanding, calling out that they had not had relevant or direct experience with the topic at hand:

My own view on migration is that I think it is a very sad and sensitive topic to talk about. I personally can’t say anything about it because my family has never been forced to move out of our hometown. My thought on it is that, each and every person, should be given a second chance at their life. If that means they are going to flee their country, they shouldn’t be stopped and told they have no rights to do so. – adetemple, Utah, US

Quotes like this illustrate another exciting potential of the Name tool. Just as students can use the tool to unpack their positionality as a means to qualify their opinions, they can also use it to detect their own blind spots, think critically about subjectivity, and learn more from those with relevant lived experiences.

For other students, the Name tool functioned as way to share more idiosyncratic parts of their identities—things like personality traits, interests, and attitudes:

I am thinking of how you write about the separation of people/friend groups from the point of view of someone who never really fit into any of them. I think this separation of people is discouraging for people who are going to a new school or group. Seeing people who already have their “thing” sports, art, math etc. it can be hard trying to find where you fit in. A question i have from this viewpoint is why is it hard for some groups of people mix with people from other groups? I think this border can also be beneficial if you have found a thing you love and want to find others that also like it. – Athens_0 (New Mexico, US) commenting on HockeyGal15’s “Everyday Borders” post

In this comment, Athens_0 expresses an opinion that is specific to her identity as a young person who “never really fit into” any social group. She goes on to ask HockeyGal15 questions that are from this particular perspective: “A question I have from this viewpoint is…” It is important for students to recognize, as Athens_0 has, that their identity, experiences, and backgrounds influence not only their understanding of an issue but the kinds of questions or wonders they have, too.

Taking a cue from Athens_0’s comment, our latest iteration of the updated Dialogue Toolkit includes a similarly structured commenting prompt to support student use of the Name tool: “I am thinking of [the topic] from the point of view of someone who… [name the particular identity/experience that is influencing your perspective on the topic].”

Educators reported that students were initially confused about the definition and purpose of the Name tool and how it differed from offering a POV. Trying out the move helped to clarify its purpose and power, however. As one educator reported, asking two students to Name the sources of their conflicting perspectives on a public issue in an in-class discussion helped each student listen to one another with more respect.

The jury is out on whether students in our expanded dialogue tools pilot feel any more confident when it comes to expressing their points of view and challenging others’, or if they better understand the ways in which their points of view are shaped by their own positionality. However, since the project’s inception, many students have shared that a major strength of Out of Eden Learn is the diversity of perspectives they encounter. These three new tools are scaffolds to support more nuanced (and, at times, more critical) dialogue around such perspectives. As OOEL student Hockeygal15 commented on a peer’s culminating Collecting Our Thoughts on Migration post:

“…I think it is awesome how you included how important it is to connect with people from around the world because in my opinion, it was the best thing … that we could learn and hear each other’s thoughts and ideas, and whether to agree or disagree.”

As you support your students in using our new dialogue tools, we hope you’ll draw inspiration from the examples shared here. Additionally, we have developed a resource, OOEL Dialogue Tools in Action, containing further examples of these new moves—and all nine of our Dialogue Toolkit moves.

d huts or simple unfurnished brick houses. They were mostly small-scale farmers and labourers. At school the children learned many things, not just from books, but also by exploring, creating, imagining, tinkering and through dialogue and reflection. At the end of every school day the children cleaned the campus and made sure to keep their surroundings neat, colourful and beautiful.

d huts or simple unfurnished brick houses. They were mostly small-scale farmers and labourers. At school the children learned many things, not just from books, but also by exploring, creating, imagining, tinkering and through dialogue and reflection. At the end of every school day the children cleaned the campus and made sure to keep their surroundings neat, colourful and beautiful.

One day a man and a woman arrived at the gate of this remote school or free space. The man was Paul Salopek and he was accompanied by his walking partner Bhavita. Paul came walking all the way from Ethiopia and was on his way to Patagonia. He was curious to learn about people and places across the globe and write stories about them to share with the wide world. His long traverse was called ‘Out of Eden Walk’ and brought him to many unknown areas, just like the village where Loka’s school was emerging. Paul spent some days with Loka’s students, and the children were amazed by his journey. “Why walk by foot, why not use a car?” a puzzled student asked. Another wondered what Paul thought about Bihar – a state often depicted in mainstream media as dangerous, corrupt and poor. “Bihar is Beautiful” he said, “and the people are kind and welcoming.” Everybody at Loka was inspired by Paul’s story and presence, and his choice to give up everything and live a different life. Likewise, Loka had touched Paul’s heart, it seemed, as just over a month later he returned with a wonderful group of researchers from Project Zero, a research center at Harvard University. Every couple of years Paul met with them to have a conference about Out of Eden Learn (OOEL), an online platform for cultural exchange the researchers developed which is linked to Paul’s Walk.

One day a man and a woman arrived at the gate of this remote school or free space. The man was Paul Salopek and he was accompanied by his walking partner Bhavita. Paul came walking all the way from Ethiopia and was on his way to Patagonia. He was curious to learn about people and places across the globe and write stories about them to share with the wide world. His long traverse was called ‘Out of Eden Walk’ and brought him to many unknown areas, just like the village where Loka’s school was emerging. Paul spent some days with Loka’s students, and the children were amazed by his journey. “Why walk by foot, why not use a car?” a puzzled student asked. Another wondered what Paul thought about Bihar – a state often depicted in mainstream media as dangerous, corrupt and poor. “Bihar is Beautiful” he said, “and the people are kind and welcoming.” Everybody at Loka was inspired by Paul’s story and presence, and his choice to give up everything and live a different life. Likewise, Loka had touched Paul’s heart, it seemed, as just over a month later he returned with a wonderful group of researchers from Project Zero, a research center at Harvard University. Every couple of years Paul met with them to have a conference about Out of Eden Learn (OOEL), an online platform for cultural exchange the researchers developed which is linked to Paul’s Walk.

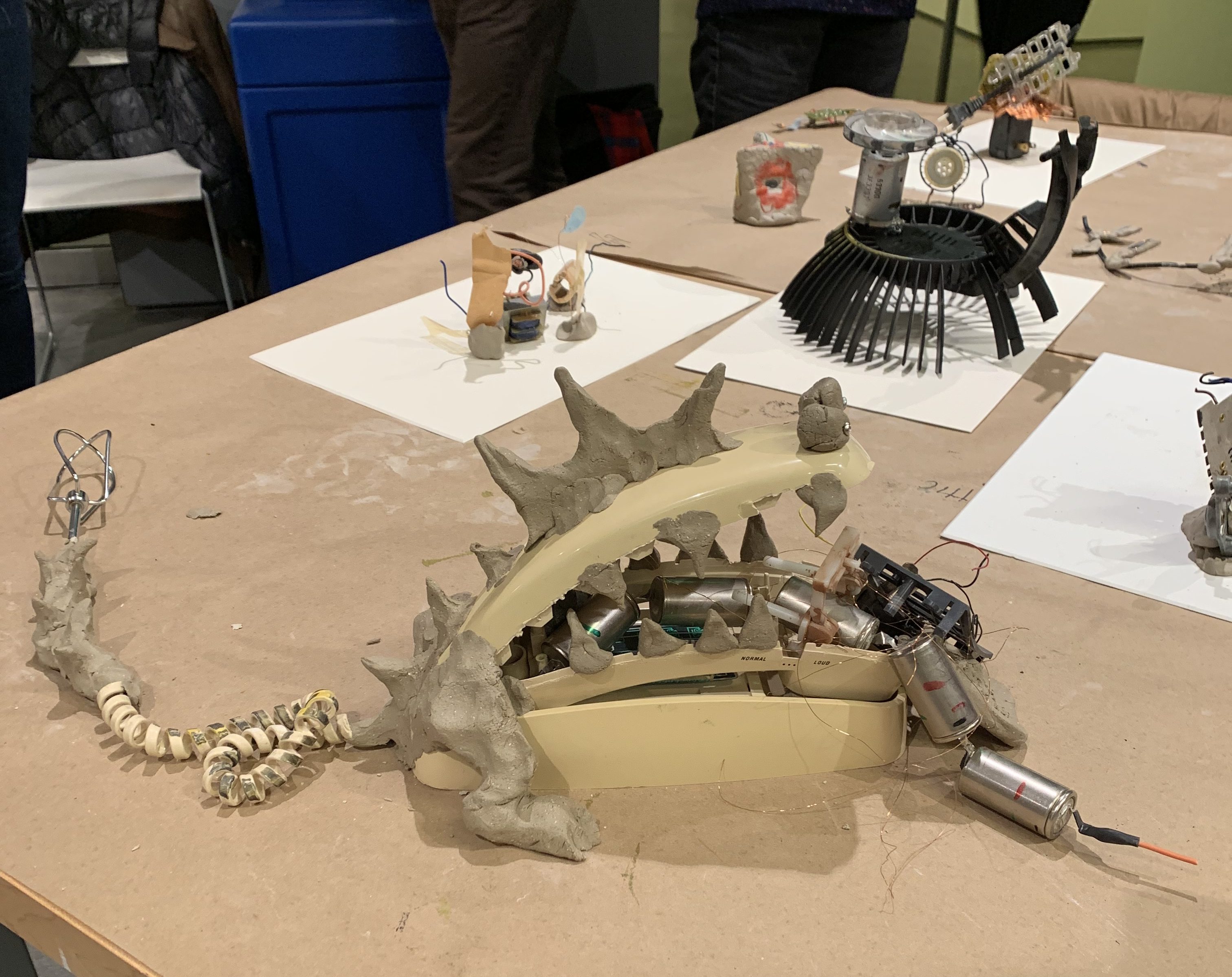

s of our economies, livelihoods, food security, health and quality of life worldwide.” (1) We also read an article about the decline of fireflies and monarch butterfly populations, specifically in Chicago. The students were struck by statements like, “Chicago and the surrounding area has already seen “significant” declines in its insect and bat population,” said Andrew Wetzler, managing director of the Nature Program at the Natural Resources Defense Council. Monarch butterflies — the orange and black butterflies that flutter around gardens and flowers in the spring and summer — and fireflies, a staple of many Chicagoans’ childhoods, are expected to be among the local insects that will be lost. Insects like butterflies and creatures like bats are pollinators, and plants need to be pollinated to produce food.

s of our economies, livelihoods, food security, health and quality of life worldwide.” (1) We also read an article about the decline of fireflies and monarch butterfly populations, specifically in Chicago. The students were struck by statements like, “Chicago and the surrounding area has already seen “significant” declines in its insect and bat population,” said Andrew Wetzler, managing director of the Nature Program at the Natural Resources Defense Council. Monarch butterflies — the orange and black butterflies that flutter around gardens and flowers in the spring and summer — and fireflies, a staple of many Chicagoans’ childhoods, are expected to be among the local insects that will be lost. Insects like butterflies and creatures like bats are pollinators, and plants need to be pollinated to produce food.

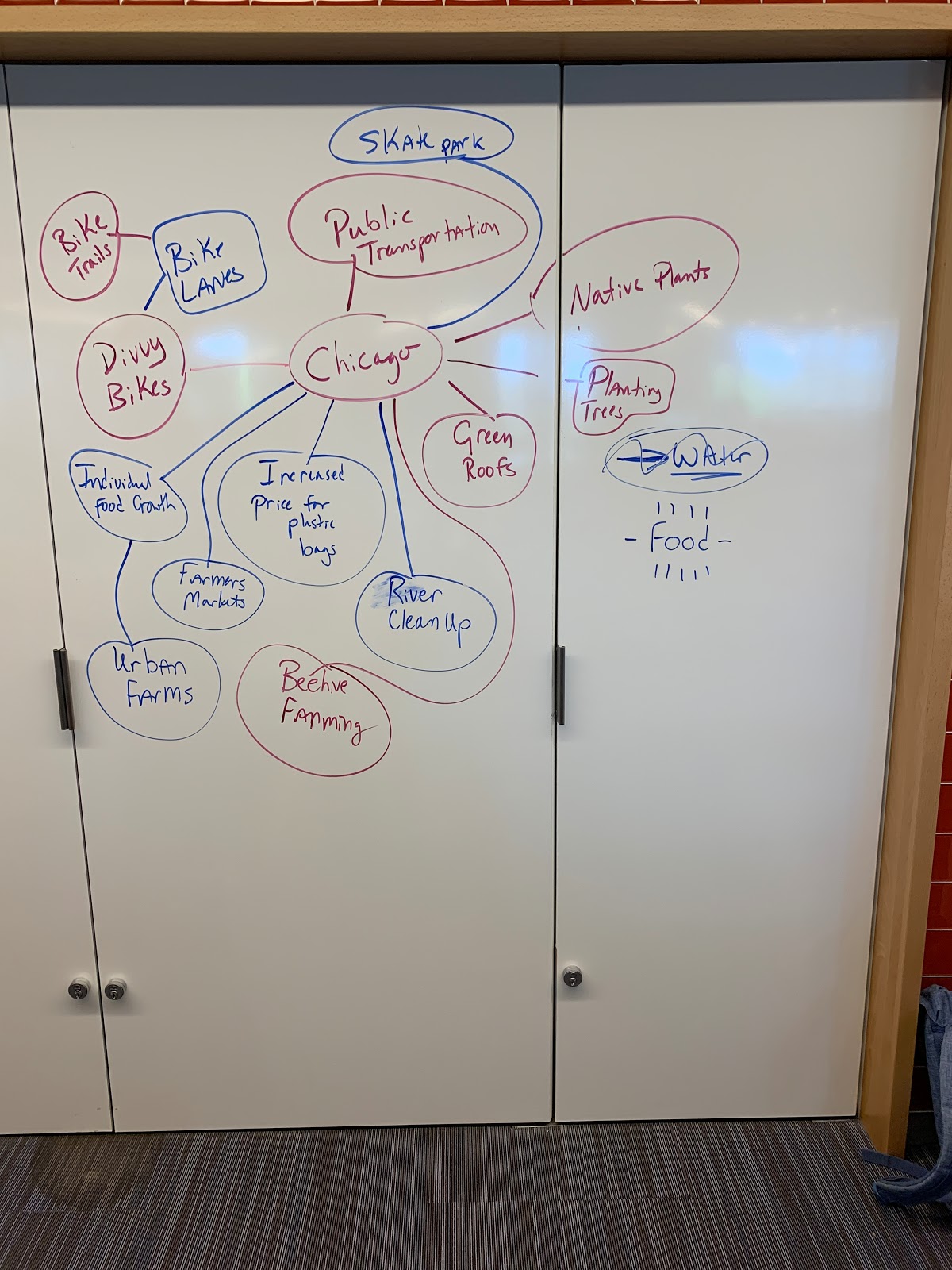

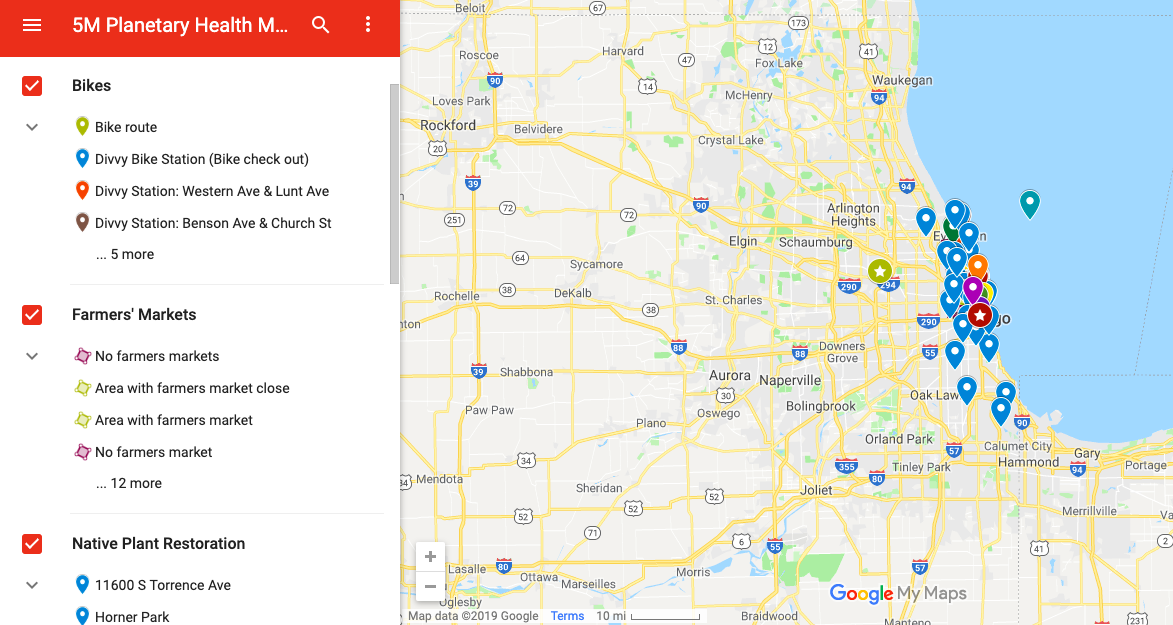

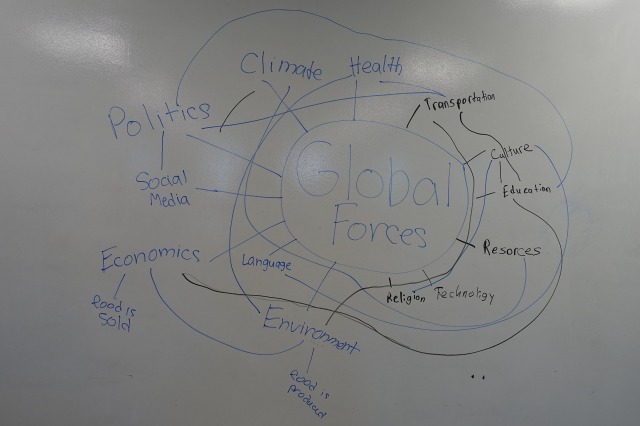

Students began by researching everything they could find that was happening at a local level, who was doing the work and what the issues were the Chicago community is trying to fix. They explored innovative ideas like robots being used to clean up the river. They discovered areas of the city that contained no farmer’s markets and were introduced to the concept of food deserts. They discovered the importance of planting native species in their own gardens and the impact that can have on pollinator populations.

Students began by researching everything they could find that was happening at a local level, who was doing the work and what the issues were the Chicago community is trying to fix. They explored innovative ideas like robots being used to clean up the river. They discovered areas of the city that contained no farmer’s markets and were introduced to the concept of food deserts. They discovered the importance of planting native species in their own gardens and the impact that can have on pollinator populations.

The second triangle points to the wide diversity of migration experiences across humanity, as shaped by different historical, geographic, and political contexts. Our analysis suggests that this aspect of understanding is enhanced when peers from different contexts share stories with one another: students commented in the surveys, for instance, that they had learned from reading different posts that migration experiences can be extremely varied. At the same time, students may notice unexpected resonances across migration stories, especially given that migration is a fundamental and ongoing aspect of the story of our human species.

The second triangle points to the wide diversity of migration experiences across humanity, as shaped by different historical, geographic, and political contexts. Our analysis suggests that this aspect of understanding is enhanced when peers from different contexts share stories with one another: students commented in the surveys, for instance, that they had learned from reading different posts that migration experiences can be extremely varied. At the same time, students may notice unexpected resonances across migration stories, especially given that migration is a fundamental and ongoing aspect of the story of our human species.

The content of the third triangle, meanwhile, has been conceptually expanded. The new wording is intended to capture students’ ability and willingness to reflect on their own relationship to and understanding of migration, and how their relationship and thinking may be evolving or developing over time, perhaps because of an experience such as Out of Eden Learn. They recognize that their own perceptions of migration are at least in part shaped by their own identities, backgrounds, and life experiences.

The content of the third triangle, meanwhile, has been conceptually expanded. The new wording is intended to capture students’ ability and willingness to reflect on their own relationship to and understanding of migration, and how their relationship and thinking may be evolving or developing over time, perhaps because of an experience such as Out of Eden Learn. They recognize that their own perceptions of migration are at least in part shaped by their own identities, backgrounds, and life experiences. This wording replaces two previous aspects: “honors and connects to others” and “asks thoughtful questions; initiates discussion”. These two previous aspects certainly captured what we observed students doing in our data but we felt they were indicative of something more important. Our choice of the phrase “Responds with sensitivity” intends to convey being attuned and attentive to what others are saying, as well as responding thoughtfully and with respect. Importantly, it invokes the act of listening.

This wording replaces two previous aspects: “honors and connects to others” and “asks thoughtful questions; initiates discussion”. These two previous aspects certainly captured what we observed students doing in our data but we felt they were indicative of something more important. Our choice of the phrase “Responds with sensitivity” intends to convey being attuned and attentive to what others are saying, as well as responding thoughtfully and with respect. Importantly, it invokes the act of listening.

program evaluation (as Bare notes) or to referencing key historical moments (as in the case of the tribal elders), but also to broader thoughts about education. Too often, the values that guide the creation of educational assessment and documentation tools are far removed from the teaching and learning environments in which they’re used, and might even be mysterious to the practitioners that use them. Even more often, learners are completely left out of the practices of documentation and assessment, and framed as subjects of research rather than as participants in the process. This phenomenon seems to run counter to notions of

program evaluation (as Bare notes) or to referencing key historical moments (as in the case of the tribal elders), but also to broader thoughts about education. Too often, the values that guide the creation of educational assessment and documentation tools are far removed from the teaching and learning environments in which they’re used, and might even be mysterious to the practitioners that use them. Even more often, learners are completely left out of the practices of documentation and assessment, and framed as subjects of research rather than as participants in the process. This phenomenon seems to run counter to notions of  This diagram is intended to evoke the metaphor of a kaleidoscope: the various parts are interconnected and can come together as well as expand or recombine in different ways. The diagram is color-coded according to three broad aspects of learning. The pink shapes represent the affective or attitudinal qualities we hope to promote among young people as they engage around the topic of human migration; the blue shapes represent the kinds of substantive understandings we want them to develop; the green shapes convey the dimensions of critical awareness that we believe to be important for navigating this topic in insightful and sensitive ways. At the center of the diagram and stretching across it are the core design principles of the Out of Eden Learn model, which we believe help to foster the attitudes, understandings, and capacities identified.

This diagram is intended to evoke the metaphor of a kaleidoscope: the various parts are interconnected and can come together as well as expand or recombine in different ways. The diagram is color-coded according to three broad aspects of learning. The pink shapes represent the affective or attitudinal qualities we hope to promote among young people as they engage around the topic of human migration; the blue shapes represent the kinds of substantive understandings we want them to develop; the green shapes convey the dimensions of critical awareness that we believe to be important for navigating this topic in insightful and sensitive ways. At the center of the diagram and stretching across it are the core design principles of the Out of Eden Learn model, which we believe help to foster the attitudes, understandings, and capacities identified.

-

-

-

Support PZ's Reach